The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory:

The Fire That Ignited a Change in Worker Rights

Historical Context

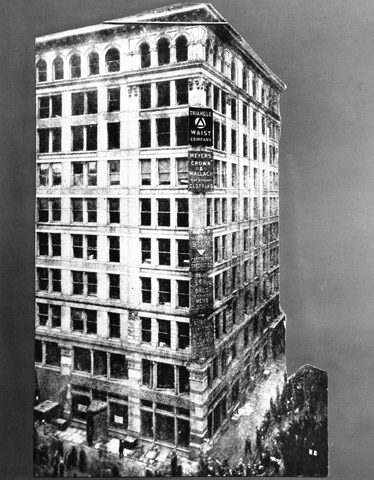

Background: Triangle Shirtwaist Factory

Brown Building (previously known as the Asch Building)

Location: Lower Manhattan, New York City

Date: 1901

Architect: John Woolly

“Fireproof” by contemporary standards

Safety Measure: One fire escape

The Shirtwaist Factory Location: 8th, 9th, and 10th floors

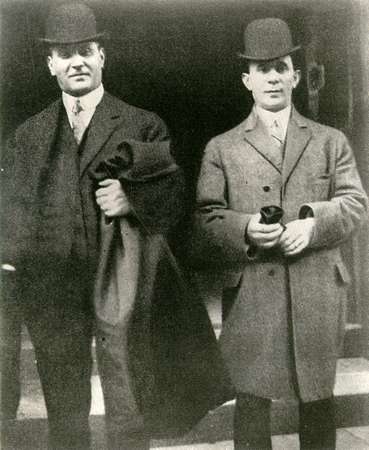

Max Blanck and Isaac Harris

Business Owners

Nickname: “Shirtwaist Kings”

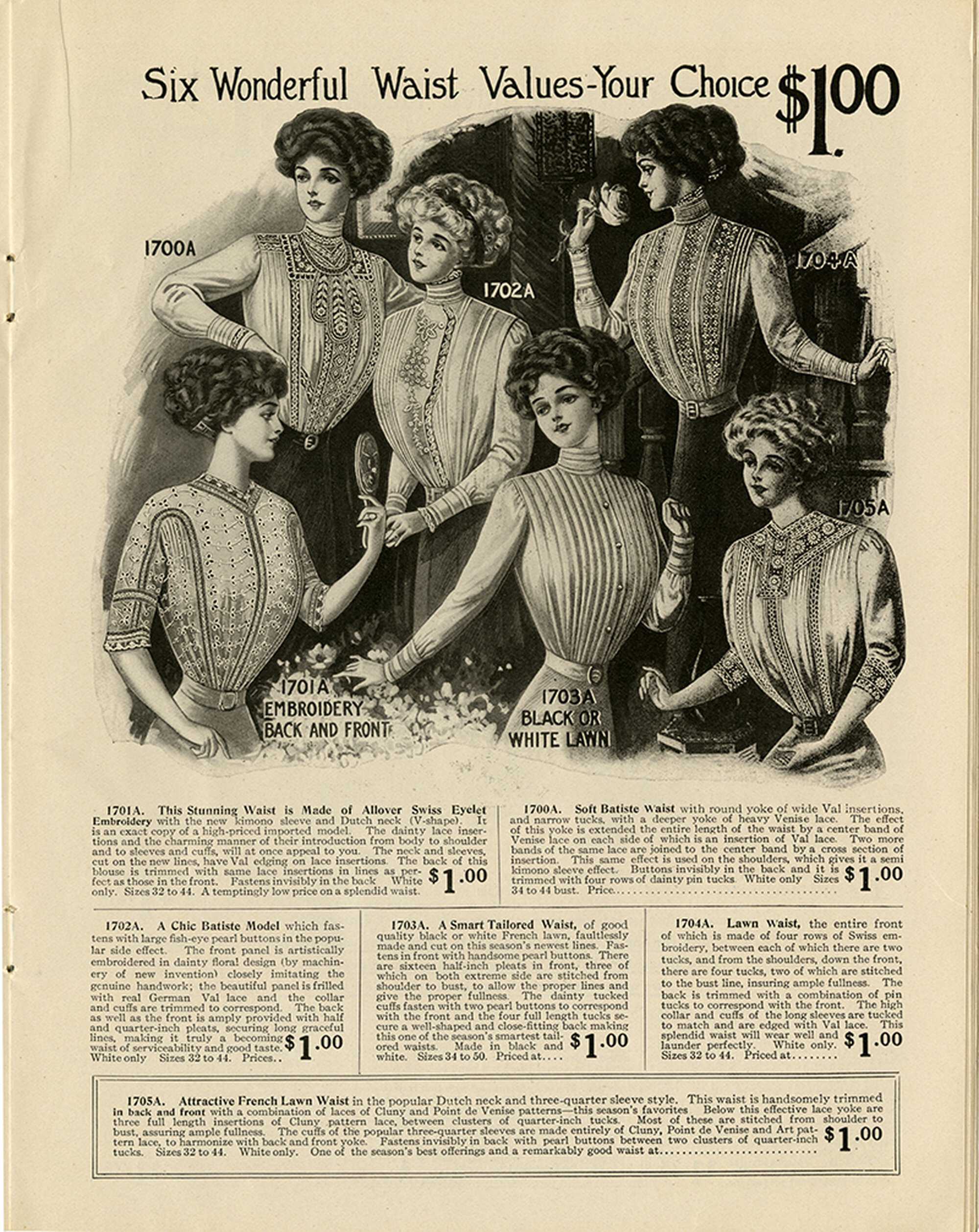

Shirtwaists, at the time, were a fashionable and popular basic article of women's clothing and transcended its accessibility among classes.

“Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory," 1910. Kheel Center, Cornell University, Image Identifier 5780pbx39ff19.

"The Asch Building was one of the new 'fireproof' buildings, but the blaze on March 25th was not their first. It was also not the only unsafe building where so many young immigrant women worked six or seven days each week," Photograph. March 25, 1911. Cornell University, ILR School, Kheel Center for Labor-Management, Documentation & Archives, Triangle Factory Fire Online Exhibit.

“As you will note, the days were long and the wages low -- my starting wage was just one dollar and a half a week -- a long week -- consisting more often than not, of seven days. Especially was this true during the season, which in those days were longer than they are now. I will never forget the sign which on Saturday afternoons was posted on the wall near the elevator stating -- ‘if you don't come in on Sunday you need not come in on Monday!”~ Pauline Newman

Fashion Institute of New York/SUNY.“Six Wonderful Waist Values-Your Choice $1.00.” Advertisement, 1910. PBS: American Experience.

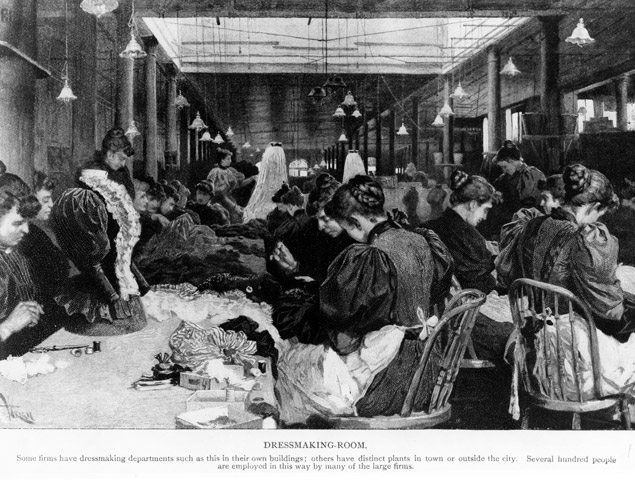

Working Conditions

In order to keep up with the high demands of production, Blank and Harris kept wages low and hours long to maximize profit and output.

During working hours, workers were…

Subjected to very unhygienic and unsanitary conditions, including poor ventilation.

Allowed a 30-minute lunch break during a 12-hour shift.

Expected to work 84 hours weekly for $6/week.

Locked on the factory floor.

Prohibited from using the restroom.

“As I look back to those years of actual slavery I am quite certain that the conditions under which we worked and which existed in the factory of the Triangle Waist Co. were the acme of exploitation perpetrated by humans upon defenceless (sic) men women and children -- a sort of punishment for being poor and docile” ~ Pauline Newman

“They were also charged 'rent' for the chairs they sat in eight to thirteen hours a day, six days a week, in overcrowded rooms” ~ Amy Kolen

Immigrant Experience

The factory workers included roughly 500 Jewish and Italian immigrants, the majority women. They were primarily between the ages of 13 and 23. Many came to America in search of a better life but were instead exploited and viewed as a form of cheap labor. It was easier for them to exploit young and vulnerable girls in a place alien to them. Despite facing poor conditions, these immigrant workers avoided speaking out in fear of losing their jobs. Labor unions were their only hope.

“What drove people like Isaac Harris to exploit their fellow immigrants, fellow Jews who, like themselves, had fled from tyranny in their homeland to a life that promised, as Grandma said in her letters, streets paved with gold?”~ Amy Kolen

“There had never been a fire drill, nine tenths of the employes cannot speak English and yet he [the fire marshall] found no signs in Yiddish or Italian pointing to the exits.”~ The Yakima Herald

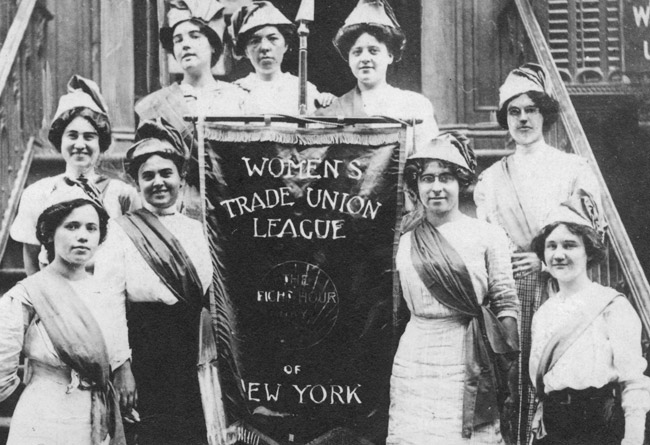

Attempts To Combat Exploitation

On November 23, 1909 the International Ladies’ Workers Union organized a strike made up of 20,000 immigrant women workers Their grievances included better wages, shorter workweeks, and extra pay for overtime. The owners’ response was violent. Blank and Harris hired thugs and police officers to fight and arrest strikers. The outcome resulted in injuries to protesters and no gains for their demands.

"The strike was just as bad. Because we were really licked. We were in - arrested three thousand times. Every time we went picketing and we got arrested."

~ Dora Maisler, survivor

"If the union had won we would have been safe. Two of our demands were for adequete fire escapes and for open doors from the factories to the street. But the bosses defeated us and we didn't get the open doors or the better fire escapes. So our friends are dead."

~ Rose Safran, survivor